Designing awesome things for people means teasing out insights into human behavior from mountains of data. Julie Zhuo was over at ZURB recently and shared how Facebook drives decisions by data, most often with relatively small impacts. At ZURB we've confronted massive data sets in the form of billions of Photobucket photos, millions of NYSE market transactions per minute, and tens of thousands of genes in the human genome with 23andMe. Since 80% of statistics are made up on the spot (as 4 out of 5 dentists agree), how do you find patterns in your data to help you make the right changes and not screw it all up? Consider these three lies that are easy to run into with your data:There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics.

- Mark Twain

1. Asking the wrong questions

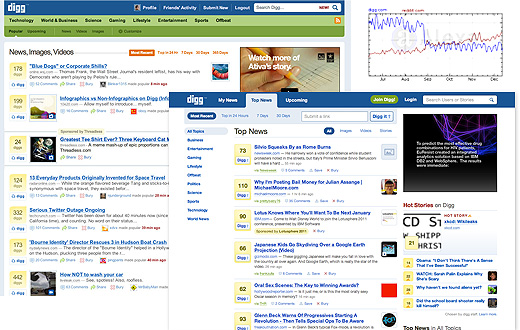

The worst thing you can do is ask no questions when researching your data for answers. Second to that, though, is being lazy. Ask boring or loaded questions and they can lead to self-fulfilling results (wishful thinking that's bound to meet a cold, hard reality). Your expectations can subconsciously influence small but important decisions you make along the way--take Digg.com for example. Digg.com's Version 4 redesign focused on things at the expense of existing customers and pageviews tanked 37%

Digg.com's Version 4 redesign focused on things at the expense of existing customers and pageviews tanked 37%

Out of 200+ Million pageviews in July, only 0.4% was from upcoming (yes, that's less than 1/2 of a percent). I definitely see the fun behind wanting to see stories just before they jump...That's an odd perspective to take given the role of that page for so many die hard users. It seems Rose and team were asking questions wishing for answers. Along the way they forgot the people they served and didn't ask the tough questions they would the day the new site launched. Three months later, Digg.com has shed 37% of its pageviews and lost its lead over competitor Reddit.com in a catastrophic fall.

2. Using bad data

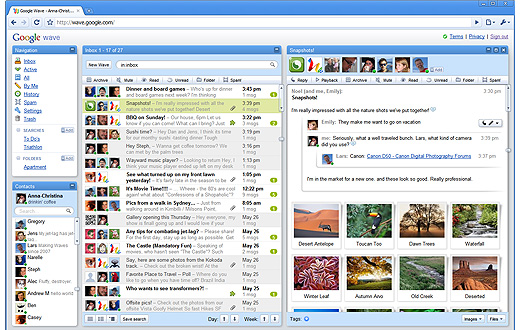

Good questions help avoid selecting bad data, but it's still easy to get lazy and sample something too small or too favorable to the answers you hope to find. It's interesting to look at what constituted a'oebad dataa'' in the case of product flop Google Wave. From the Wave team's blog and interviews its clear they are very smart people who spent a lot of time focusing on their own code and with tracking and responding to the concerns of early adopter developers. Noble pursuits, but they don't add up to the concerns of everyday people who were excited by the promise of a live, conversational document. With so much complexity in Wave, the Google team needed a laser-like focus on metrics that illustrated customer problems to build a true replacement for email.

With so much complexity in Wave, the Google team needed a laser-like focus on metrics that illustrated customer problems to build a true replacement for email.

3. Misinterpreting results

Even if you're asking the right questions and mining the right data, there are more lies you can fall into. First, be sure that pattern in the data you think you see actually exists. Humans are pattern-recognizing animals, sometimes to a fault. Even if you recognize legitimate patterns in your results, you still have the burden of interpreting "why" those results exist and presenting them to other people to drive decisions. Kevin Rose reached for data in defense of the Digg redesign, even calling it a success:Usage looks extremely good (ie. more people registering (43,000+ new users yesterday), digging, consuming, clicking, following, etc.)This is so easy to do, but you can't ignore an obvious bad situation or change the answers you hope to find to fit your results after the fact. Rose quoted activity stemming from the short-term spike in awareness and traffic from the buzz around their relaunch. He was no doubt comfortable measuring those metrics, but did so at the expense of asking tough new questions. The questions you ask, the numbers you look at, and the patterns you see all effect whether the numbers you end up using actually help people, or just end up lying to them.